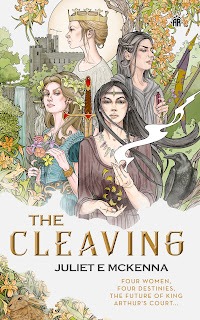

Juliet E. McKenna

Angry Robot, 11 April 2023

Available as: PB, 400pp, e

Source: Advance copy

ISBN(PB): 9781915202222

I'm grateful to Angry Robot for sending me a copy of The Cleaving via NetGalley to consider for review.

Arthurian retellings broadly seem to adopt one of two approaches. The first is to ditch the fantastical elements and look for a foothold in history, however tenuous, typically casting Arthur as the military leader of the native Britons against the invading Saxons. This is the approach I remember from innumerable documentaries when I was growing up in the 70s and the 80s.

McKenna's reimagining follows other approach - taking the familiar medieval sources but adapting their framework. She makes a nod towards the historical approach by drawing a linguistic distinction between the Cornish language and the "English" spoken in Winchester. But when "Saxons" come raiding the "English" she doesn't worry too much about trying to explain the distinction. Similarly, this story accepts noblemen with elaborate plate armour, all called Sir Somebody, riding the countryside of Southern Britain and retiring periodically to the court at Camelot. They are often about business driven by magical interference, although (not least, I'd imagine, to keep the book to manageable proportions) many of the incidents are left out.

That all works very well with what we expect of an Arthurian tale ("Arthurian" isn't quite the right term here, but I'll come back to that) from Mallory himself to TH White. But don't be deceived by the surface impression, this retelling is actually very different.

To begin with, I felt that here there is a much clearer overall narrative, rather than a procession of wonders. And that isn't a narrative about Arthur, indeed in some ways he's almost incidental, or the Holy Grail. Yes, Arthur desires to be High King of Britain, and strives to achieve that, but behind him, there is a desperate - and actually more interesting - conflict over the role of magic. Nimue, one of the Hidden People, from whose viewpoint the story is told, sees magic as dangerous to mortals and seeks to limit its role (in line with the principles of the Hidden People). Merlin, and some others of the People, want to use it to establish Arthur's throne, allegedly so he can be a bulwark against magic running wild although sheer desire for power may also figure here.

The various eruptions of magic into the courtly business of Camelot then feature as overspills from this contest, with the balance of advantage swaying to and fro throughout the book, rather than a series of discrete, if dramatic, incidents. That gives the book a coherence, a drive, which keeps the reader turning the pages - and worrying about what will come next.

And there's a lot to worry about. The other difference here is the telling of the story from the point of view of Nimue, a character who does feature in the canonical stories, as the enchantress who seduces and imprisons Merlin. Here though we see Nimue's perspective throughout, from the early sections set at Tintagel Castle, dealing with Uther's rape of Ygraine, to her struggles with Merlin, to an endgame in which Nimue together with other powers is forced to take responsibility for the future of Britain rather than allowing warfare and anarchy to continue.

It's a very anti-heroic book - in the sense both that it explicitly disavows the simplistic "Arthur is the foretold King so anyone standing against him is evil" but also in the way that it acknowledges, indeed celebrates, the complexity of life: all those feats of arms, for example, don't just happen, the provisioning and cooking must be organised. Camelot - and the other fortresses - need to be managed and operated, a task falling on the women here, not helped by the tendency of Arthur and his ilk to announce tournaments or depart on quixotic quests at the drop of a gauntlet. Or by their proclivity for decreeing the marrying-off of the chatelaine on a whim. Napoleon Bonaparte may have understood that an army marches on its stomach, but is twelve hundred years earlier and the men haven't yet learned that lesson.

Possibly I was a bit quick earlier to place this book in the "non historical" group of retellings. Amidst all the controversy about British history in the late-antique period and about "Saxon" invasions and the evolution of "England" one point that is easily missed is the daily routine that must have continued - growing food, mending fences, preparing food, spinning and weaving, caring for children and the old - things without which the land would have soon been a desert. That activity finds its place in The Cleaving where its importance is fully acknowledged, making this book - for all its magic and wonders and mounted knights - historical at a much more fundamental level. Instead of working to find a slot for an Arthur in British history, McKenna is I think restoring a place for women and women's activity. This book is perhaps not Arthurian so much as Nimuean - celebrating the making of an ointment, the planning of a feast or care for an orphaned child, all things that belong in history as much as swordplay and marching.

So I think this is something rather different - as well, of course, as being a thoroughly good read, the pared-back story keeping up a good pace and relying on excellent characterisation and a real sense of moral ambiguity (the mess of prophecy and manipulation that Merlin has created being deeply inimical to any clear sense of right and wrong). Rather than the triumph of good, in The Cleaving the reader is just left hoping that the women we meet will avoid their possible awful fates, come through and win some peace for themselves and their country.

All in all, a masterpiece.

For more information about The Cleaving, see the publisher's website here.

No comments:

Post a Comment