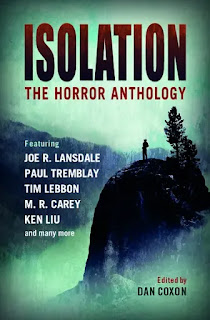

Isolation

Edited by Dan Coxon

Titan Books, 13 September 2022

Available as: PB, 400pp, e

Source: Advance copy

ISBN(PB): 9781803360683

I'm grateful to the publisher for an advance copy of Isolation to consider for review.

This anthology is very timely. With various periods of covid lockdown in most of our recent pasts, the experience of isolation - its advantages and disadvantages - have been much discussed. While the conversation will certainly continue, and experiences clearly varied according to circumstances, personality and location, it's clear that many of us were not fans. Nor was the experience evenly distributed. Many office workers were expected to do their jobs from home, perching on beds with laptops or if more fortunate, taking over a spare bedroom, but others had to continue, often bearing a disproportionate share of the virus risk.

Speculative fiction offers a powerful lens to examine these impacts and inequalities - which is just what Coxon's new anthology does, delivering some disturbing takes from both well-known authors and some new voices. And as the chill mists of Autumn gather, the horrific side of things seems particularly appropriate. The anthology contains a broad range of stories and as well as enjoying familiar voices, reading it has opened up my TBR to several writers I hadn't read before - which is a GOOD thing (although my bank may not agree).

Among my favourite stories here, Alison Littlewood's The Snow Child opens the collection with highlighting some dangers and sadness inherent in being left alone. Nobody, in my view, does snow-bound horror as well as Littlewood. Her A Cold Season and Mistletoe are creepy, compelling masterpieces of the genre and she repeats the effect in miniature in The Snow Child, a glorious, enclosure-laced story of a mother and a daughter in a remote cabin close to the Arctic circle. Things have gone badly wrong out there, and Tilda feels guilty that she left her mother to cope alone. Slowly though, guilt gives way to fear, as it must in horror. A chilling start to the collection.

Another of my favourites was Second Wind by M.R. Carey. Not apocalyptic except in the curious sense that the dead no longer remain dead, we follow a successful banker determined to endure, who sees that he has a safe lair prepared, a place he won't be disturbed... until the local homeless find their way in. I loved this story that poses questions about priorities, about what makes us what we are. And there's Letters to a Young Psychopath by Nina Allan, to show that isolation is not always a physical thing but may be an aspect of personality. Written as advice to an unknown reader, this story explores the bounds between what you do and what you nearly do. The writer explains freely where he's coming from and what he's done - and might yet do. The isolation is in his (it's always a him, right?) place in the world, in his head, not in his social position or physical location. It's a moral isolation, but it still has consequences. A chilling and genuinely upsetting story.

I also highly rated Ready or Not by Marian Womack. This blends a really chilling sense of isolation with a vein of threat. Alison is alone in her house, actually her parents'-in-law house. Her partner is missing - we're not quite sure how - and as a German citizen in the UK post Brexit she already feels out on a limb. Julian's behaviour has not been supportive. The old woman living next door radiates malice. The story makes Alison seem to shrink and fade, pressed as she is by so many forces that seem determined to erase her identity and autonomy.

Among the stories that do reference the pandemic, or its aftermath, Friends for Life by Mark Morris stands out. It's a story of loners getting together for one night week to enjoy a little companionship and seems almost heartwarming, until it takes a turn. Daniel is still mourning his mother - whose care he'd devoted himself to - and Morris adroitly plants doubts about that whole situation, before taking things to a much darker place than I'd expected. Chalk. Sea. Sand. Sky. Stone. by Lynda E. Rucker is set during the first lockdown, when Claire, a young (and recent) widow but a 'geriatric' (ie over 40) mother-to-be, retreats to the safety her grandmother's house by the sea, taking advantage of the isolation brought by the pandemic to explore her grief in private. A simple story, at first sight, until another, jarring element intervenes. Rucker expertly teases this, leaving us to wonder whether it's an alien, intruding thing or something that comes from Claire herself? This one haunted me.

The Blind House is a story of a type I suspect we will see more of - Ramsey Campbell uses the now common experience of home working to evoke horror (as well as to poke fun at the publishing industry which may be a more particular trop). Our hero, Simon, is a proofreader who has taken himself off to work remotely from what seems a most unappealing apartment block. As in Ready or Not, there is a distinct spirit of place, a spirit draws in not only the reader but Simon too. Campbell's skill with slightly off-kilter speech patterns and multiple layers of meaning allowing Simon to, as it were, deliver his own commentary on his fate even before he suffers it.

Of course, an isolated character surviving after some sort of apocalypse is a fairly common feature of horror, and there are several of them here. Lone Gunman by Jonathan Maberry begins with the hero buried under a pile of corpses, one man left standing (as it were) amidst a swarm of monsters. As he flees from situation to situation, the question is posed starkly - what to do? I enjoyed seeing Maberry work through the answer. Full Blood by Owl Goingback is a full-blooded (sorry) post-apocalyptic story written from an Indigenous perspective (if only those Western scientists had consulted local knowledge before they meddled...) The isolation is of the last-man-standing sort, the ending certain, the interest in how we get there. The Long Dead Day by Joe R. Lansdale is another zombie story, nicely echoing How We Are by showing again that isolation may not be something we can sustain, whatever that leads to.

If there's a timeline in apocalypses, Fire Above, Fire Below by Lisa Tuttle might come next. If you could know of the horrors that were coming - would you want to? My answer would be "no"- worry about the future can be numbing when one feels powerless to affect it - but Tuttle poses the question, what if you could affect it (maybe, a bit?) The curse of prophecy is well known yet Tuttle gives it a new spin with a twist of foreknowledge for her protagonist as things get worse and worse. But her knowledge is as in a glass darkly, she may glimpse outcomes of this or that but misses the big picture, leaving her truly alone.

The prospects of those last survivors never look good, but a story can still allow them space for some final reflection or realisation as in There's no Light Between Floors by Paul Tremblay which takes place on the cusp of a disaster, a man waking in the midst of destruction and struggling to accept the meaning of what he's going through. It's story in which the reader will soon work out what's going on, leaving us to watch in pity and dread as those going through the end of the world struggle to keep up.

Of course, something may survive the collapse of society. In Across the Bridge, Tim Lebbon gives us a choice of futures. Decades after a calamitous infection, or perhaps simple environmental disaster, the last humans are either rebuilding a new, more harmonious way of life in rural bliss, or sheltering from the storm in a blasted, withered hellscape. These things can't both be true, surely? But isolation can play tricks with reality... a truly though-provoking story with no easy way out.

I'm something of a fan of what I call "unexplained horror" - scenarios far away from even the weird but self-consistent setting of a pandemic or monster plague, scenarios that you simply have to accept and work through. Two here are Under Care by Brian Evenson and The Peculiar Seclusion of Molly McMarshall by Gwendolyn Kiste. Under Care explores a creepy hospital. Creepy hospitals! What could be worse? Imagine being a patient in one of these - never seeing anyone but the mysterious nurse, beginning to doubt who you are and why you are there. Until you find out. A real, incrememental horror, building on that sense of unease many of us feel at the sterile smelling, squeaky floored environment. In The Peculiar Seclusion of Molly McMarshall by Gwendolyn Kiste, Molly herself is seen little, in fact she vanishes, fades, ceases to be quite as others are, in her own house. (Maybe shades of lockdown after all?) Unlike in other stories in this book where a character loses identity when overlooked by wider society, here the outside world takes a prurient interest in what has happened (a bit of satire on the online world and the appetite for 24 hour news perhaps there) but it might have been better for them if they hadn't?

You can't have horror without a decent monster or two, and the best monsters are those who evoke sympathy, I think.

In Solivagant by A.G. Slatter we have a sad horror, a story where one may have sympathy for a monster. While this is a fantasy story featuring a supernatural monster, the isolation here is very familiar, a young woman separated from her family and friends by a man, left with nowhere to run and nobody to turn to. It's doubtful whether the supernatural horror is the greatest threat here, but in a brilliant study of character and circumstance we are given a little hope that there may be a way out.

How We Are by Chịkọdịlị Emelumadu is a story of witches. Gifty is isolated by choice, as the bearer of a family curse (and because she is under the thumb of a watchful grandmother). A reminder that isolation may serve a purpose, we see her toy with relaxing the constraints she's under - but can that come to any good?

In Alone is a Long Time by Michael Marshall Smith we might think that the character who is isolated here is "Mr Jones", the client of carer Karen. In a sense that's true, but in parallel with the gradual revelation of Karen's (and Jones's) situation and lives, there is a suspicion of something else at play and so it proves. Alone is, indeed, a long time. A well-paced and absorbing story.

Finally, So Easy to Kill by Laird Barron is very much a hard SF horror, spanning unimaginable eons almost to the end of the universe and featuring god-like beings who, while recognisably human in their failings, have become so... much. Still though, they play their games and in this story motives, histories and potential are nested and layered until neither we nor the protagonists can see where things are heading.

So many ways to be alone. So many futures and choices. The stories in Isolation truly explore the richness and dread of being by oneself, whether that's permanent or temporary, voluntary or forced or, indeed, physical, spiritual or temporal separation.

No comments:

Post a Comment