The Collapsing Wave (The Enceladons Trilogy, 2)

Doug Johnstone

Orenda Books, 14 March 2024

Available as: PB, 257, e, audio

Source: Advance copy

ISBN(PB): 9781916788053

Doug Johnstone

Orenda Books, 14 March 2024

Available as: PB, 257, e, audio

Source: Advance copy

ISBN(PB): 9781916788053

I'm grateful to Orenda Books for sending me a copy of The Collapsing Wave to consider for review, and to Anne Cater for inviting me to join the book's blogtour via Random Things Tours.

The Collapsing Wave is the sequel to The Space Between Us - the title comes from the quantum mechanical notion of wavefunction collapse, when an observation resolves an experiment into a known state, but it also cleverly alludes to events in the story. It picks up events six months after the end of the previous book, which was hopeful, if ambiguous, but now everything seems to have gone to s***. Ava, who escaped from her controlling, abusive husband, is now on trial for his murder and has been separated from her newborn daughter, Chloe. Lennox and Heather, who also bonded with the alien they called sandy, have been kidnapped and are being held in what I will emphatically state are illegal circumstances at a secret US facility on Loch Broom, where the Enceladons (Sandy's people, refugees from the moon Enceladus) are being studied (read: tortured).

The first half of the story is therefore pretty rage-inducing with the wicked and the venal going about their business pretty much unmolested. It didn't do my blood pressure much good, I can tell you, and I would love to have a few minutes in private with Turner, Gibson or Carson: cowards and bullies all. In contrast, as ever, our heroes are somewhat conflicted, unsure of their best course of action, and hampered by little things like moral scruples, empathy and guilt. ("The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity").

In a sense it doesn't help that the gifts the Enceladons bring are all about empathy, and sympathy, about a way of being and living that challenges the cult of individuality. They therefore represent a threat, whether the humans know it or not, that is more fundamental and insidious than the "invasion of the little green men form Mars" trope. The example of a better way of being implicitly judges Earth's ways, and shows the current greed-driven model of society, growth and progress to be wanting. In this respect, I find Johnstone's story to be rather like a reverse Gulliver's Travels - just as Jonathan Swift pitilessly highlighted the faults and failings of his own society by taking a specimen of that society and comparing him with various idealised nations, so Johnstone brings a benign, cooperative creature to, ultimately, shame us and our doings.

It won't end well. It can't end well. Our heroes are imprisoned, dark deeds are afoot and the resistance, if I can use that term, painfully weak and fragmented. (One of Johnstone's themes is how supposedly democratic social media simply floods the channels with a deluge of lies, confusion and conspiracy theories, swamping the truth. There is some interest in what's going on in that secret base, with a peace camp of sorts outside, but I can't help feeling that in the high days of activism there'd have been telephone trees and samizdat-style newsletters getting the word out, and successful raise on the base to challenge the authorities).

But.

BUT.

The dark powers we see don't, can't, possibly imagine the strength of an alternative social model. Imposing pathetic labels on things they don't understand (they call the sea creatures from Enceladus "illegals") they fail to understand what they are dealing with, leaving some, slight, margin for a ragtag group of the wise and the just to succeed. Maybe. If the first half of the book was enraging, the second is really, really nail-biting and I will say NOTHING about what goes on here and what might happen in the next book.

I should assure you that The Collapsing Wave isn't just a moral fable, though it is a powerful one. It's a novel of characters too, with each member of the little group an individual who has lived a lifetime and has the knocks to show for it. Even Lennox, who is "only", 16 has been through stuff. You can read this book for the protagonists alone who are, every one, fascinating, quirky, real and loveable.

All in all, a superlative novel with great moral force, an urgent book, I think, in view of world polictis and the state of the planet. A cosmic, world-shaking novel form Johnstone, one I'd strongly recommend.

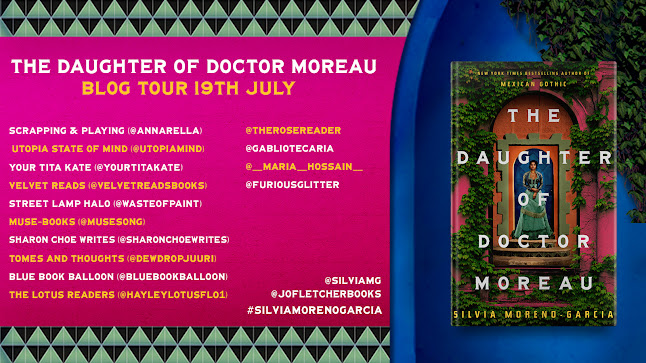

For more information about The Collapsing Wave, see the publisher's website here - and of course the other stops on the blogtour which you can see listed on the poster below.

You can buy The Collapsing Wave from your local high street bookshop or online from Bookshop UK, Hive Books, Blackwell's, Foyle's, WH Smith, Waterstones or Amazon.