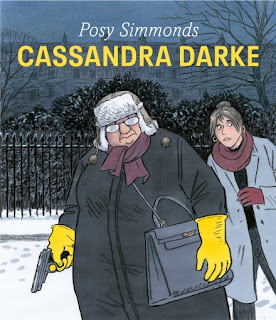

Cassandra Darke

Posy Simmonds

Jonathan Cape (Vintage), 2018

HB, 94pp

This book was a Christmas present (thank you!)

In Cassandra Darke, Simmonds uses the graphic novel format to create something resembling a scrapbook, juggling both panels and chunks of narrative (which sometimes contain, or flow round, single drawings or panes addressing points in the text, or linking with pictures elsewhere in the book). It's told from different perspectives, with the main protagonists (Darke and her niece Nicki) unaware till the end of some parts of each others' story. This reinforces their different points of view, oddly building sympathy for these very different women (who don't actually like each other very much).

Darke is a London gallery owner, something of a monster - snobbish, offensive, aggressive to everyone and, as soon emerges, not above breaking the law. She's also magnificent - unapologetic about how she lives her (fairly unconventional) life, she refuses to be defined by others' expectations of, and assumptions about, her.

What she isn't, though, also matters a lot - Cassandra doesn't really 'do' people and has no patience, especially, with the young. So her stepdaughter Nicki coming to stay always seemed likely to end badly.

And it does.

As the story opens - with Darke's, er, dark secret, discovered - that period is coming to an inevitable end so we get Cassanda's conclusions about it first, but Simmonds then hops back to show what had been going on, including things Cassandra doesn't yet know, before returning to the consequences in the present. In between, she cooks up a complex, fast moving tale encompassing, among other things homelessness, male violence towards women, criminal gangs and the 'empty quarter' of London where luxury flats lie empty in the ownership of foreign oligarchs. Through it all, Simmonds' evocative pictures transport one to all these different Londons - whether to Cassandra's sleek, modern-styled house, to pubs and bars where chancers rub shoulders with upright citizens and outright villains or to the even grubbier areas (where Cassandra really meets trouble).

It is a powerful book, clearly inspired partly by A Christmas Carol (the misanthropic central character forced to accept that they are, indeed, part of humanity, the sense of redemption, some echoes and parallels in the way the story evolves) but much more than that, engaging with the realities of (especially) modern London and picking its way through social norms and conventions (watch how Billy's accent changes). The detail of the illustrations gives plenty of scope to read and reread, always with more to be found (another parallel with Dickens!)

I'd thoroughly recommend this book.

(CWs for some violence towards women and a scene with a dog).

I like talking about books, reading books, buying books, dusting books... er, just being with books.

31 December 2018

28 December 2018

Review - Transcription by Kate Atkinson

|

| Design by Richard Ogle |

Kate Atkinson

Doubleday, 6 September 2018

HB, 337pp

I bought my copy of this book.

I should have read Transcription when it came out in September but with a lot of distractions, it slipped and I picked it up to read over Christmas. Once I did, I couldn't put it down.

Atkinson's latest is, simply, masterly. It's an immersive, compelling account of one woman's war (a phrase borrowed from the title of one of her source books, sorry) and of the price she pays for it later.

Following the death of her seamstress mother, Juliet Armstrong - a bright, scholarship girl with Oxbridge ambitions - attends secretarial college instead, then joins MI5 as a typist at the beginning of the Second World War. She assigned to monitor Nazi sympathisers in 'Operation Godfrey'. This basically means transcribing covertly recorded conversations between an MI5 agent, Godfrey Toby, and the sympathisers ('the neighbours'). They think he's a German agent, allowing him to prevent them passing on useful information to anyone who might make use of it.

The story moves backwards and forwards between 1940 - those fatal weeks around the fall of France - and 1950, by which time Juliet is ensconced at the BBC as a producer of schools programmes. Atkinson plays a long game here, gradually introducing elements looking back and hinting at how the events of 1940 played out, and how they may still haunt Juliet. More is implied than said, but it soon becomes clear that she wasn't just transcribing but at one stage actively infiltrating the 'Right Club'. (This contains just the kind of ghastly people you'd expect - traitors and cryptofascists happy to collaborate with tyranny just to protect their privileged position in the world. Mostly, rather stupid people, of a type that, unfortunately, doesn't die out). That leads her into danger, at first of a rather 'Girls' own' type but soon becoming more serious - Atkinson drops more hints, about deaths, even as Juliet's role in 1950 becomes more complex too.

At the heart of the book are two mysteries. What really is going on at the BBC? With old MI5 contacts apparently popping up and threatening messages being sent, the past seems to be reaching out for Juliet, the corridors of Broadcasting House no longer safe, a series of mistakes threatening her position at the BBC. And what really was going on in Dolphin Square in 1940? Who, exactly, was on what side? Might a network of collaborators have been a useful asset for an MI5 agent wanting to hedge their bets?

As the story becomes more complicated, truth being reflected around that labyrinth of mirrors to which spy fiction is prone, Atkinson keeps the reader focussed less on the 'what' than on the 'why' and on the consequences. There are consequences; one character spells this out explicitly towards the end, but really, we've been aware of that all along. Just look at Juliet. She is a composed, resourceful and self-aware young woman - whether in 1940 or 1950 - yet continually speculates on the future, the past, her place in MI5 or the BBC, on the effect of what she did on others (especially this). Juliet is, really, our window into some very strange worlds at a time when so much hung in the balance. The story has often been told about how in May 1940, the UK wavered on the brink of capitulation, with an influential factor in favour of peace. This is not that story - the story of Cabinet debates and Parliamentary oratory - but it also is that story - the story of what ordinary (and extraordinary) people were doing and saying that lets us imagine how they might have responded had things been different.

Readers of Atkinson's last two books, Life After Life and A God in Ruins will be familiar with some of these themes (responsibility; consequences; the price that might be paid) which she also examined there, through the lens of a kind of of multiple worlds universe and she - teasingly - alludes to this I think. In the opening scenes, set in 1981, a Royal Wedding is coming, reminding me of the framing of A God in Ruins, and there's a certain amount of overlap too in the 1940s setting and in what we might imagine Juliet's later life to have been like. But this isn't a book in that world. The alternate paths taken here are choices made and fixed and then reflected on, not points that might yet go a different way in another life. That makes the stakes, I suppose, higher, and the things Juliet has done graver.

The book is tremendous fun, shrewdly observed (a great deal of this revolving around the internal politics of a bureaucracy such as the BBC or MI5 - Juliet wonders if these two are not really fundamentally the same organisation - but also taking in things such as class and the state of British food in the 1950s) and very human in the way it deals not only the murky shenanigans of espionage but with the frail people caught up in it. Monstrous as they are, there is still some sympathy for Mrs Scaife and her entourage of would-be collaborators and Quislings. While some readers may think they never really got what was coming too them, I'm not sure; they see their hopes and plans dashed and many suffer personal loss - and as we seen, the forces of the State pretty much play fast and loose with law and decency to achieve their ends.

Best of all though, this is a thunderingly good story, the kind of thing you won't want to be parted from till it's finished.

Those are the very best books, and this is among the best of them.

21 December 2018

Review - Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

Universal Harvester

John Darnielle

Scribe, 2017

PB, e-book 214pp

This is another book I finally managed to catch up with, and 'read' as an e-book. I think my experience of this book was really added to by listening to it, by the sense of complicity, Darnielle himself reading the story in an almost - almost - deadpan voice, making the most of its asides, its speculations.

In places, he refers to alleged alternate versions where something different happened and characters had quite distinct lives as a result and this gives the story a breathing, almost alive quality as do the hints that what we're told is the knowledge of an all seeing, all knowing observer with access to secrets, records and facts. (For example, in one place his characters decide to report something to the police - but, he then just in, we no that no such calls were received that evening - almost as though he had a file of evidence open on his desk).

That all-knowingness contrasts with the teasing, leisurely unwrapping of the central mystery here. Jeremy is a young man working, in the mid 90s, in a small, local video rental store in Iowa. So recent, and yet a different world, a world of clunky analogue technology on the cusp of being swept away.

One day, customers begin to return tapes to the shop, complaining that the films they rented contain... other material. Disturbing, strange material that it is hard to watch through. Gradually, Jeremy and then store owner Sarah-Jane, begin to be pulled into investigating just what is going on. We too are drawn in, learning nothing quickly but happy just to absorb Darnielle's prose: allusive, conversational, looping, deeply rooted (I think) in the prairies, the lives of ordinary people living in small towns and on grey farms and in the snows of Midwest winters. The story is as much about how Jeremy, Sarah-Jane and their immediate friends and family react to what seems a sinister mystery - how they avoid knowing and circle round the issue: the dynamics of groups of people not seeing or saying things. A lot of this book is about choosing not to know things about other lives.

And then the pitch rises and something bad happens - and Darnielle is away into the history of a certain character, taking the story into a wholly new direction, employing the same rapport, the same easy style and leveraging the trust built up with the reader to tell a rather different tale, that itself loops back and becomes relevant.

It's a book where you feel that little details count, although there is never a complete picture in which you can see how they fit. A story where the present feels very indebted to the past - whether the unknown past of the Native people who gave their names to places like Tama and Sioux City and Iowa itself, or the more recent past of which Emily wonders '...what shed'd already missed, what had gone missing from Iowa before she ever got there'.

If you ever listened to those Lake Wobegon monologues in A Prairie Home Companion and thought, 'Surely there must be something darker there?' then here it is, a breathing out, almost, of the Gothic. It is in many ways a perplexing book, a tricksy book and I see that many reviewers on Amazon and Goodreads have confessed to not understanding it. I don't think I really understand it, either, but I do get it - if that makes sense. It's one of those rare books where 'understanding' is beside the point, you simply need to experience it.

Deeply weird but also deeply satisfying.

John Darnielle

Scribe, 2017

PB, e-book 214pp

This is another book I finally managed to catch up with, and 'read' as an e-book. I think my experience of this book was really added to by listening to it, by the sense of complicity, Darnielle himself reading the story in an almost - almost - deadpan voice, making the most of its asides, its speculations.

In places, he refers to alleged alternate versions where something different happened and characters had quite distinct lives as a result and this gives the story a breathing, almost alive quality as do the hints that what we're told is the knowledge of an all seeing, all knowing observer with access to secrets, records and facts. (For example, in one place his characters decide to report something to the police - but, he then just in, we no that no such calls were received that evening - almost as though he had a file of evidence open on his desk).

That all-knowingness contrasts with the teasing, leisurely unwrapping of the central mystery here. Jeremy is a young man working, in the mid 90s, in a small, local video rental store in Iowa. So recent, and yet a different world, a world of clunky analogue technology on the cusp of being swept away.

One day, customers begin to return tapes to the shop, complaining that the films they rented contain... other material. Disturbing, strange material that it is hard to watch through. Gradually, Jeremy and then store owner Sarah-Jane, begin to be pulled into investigating just what is going on. We too are drawn in, learning nothing quickly but happy just to absorb Darnielle's prose: allusive, conversational, looping, deeply rooted (I think) in the prairies, the lives of ordinary people living in small towns and on grey farms and in the snows of Midwest winters. The story is as much about how Jeremy, Sarah-Jane and their immediate friends and family react to what seems a sinister mystery - how they avoid knowing and circle round the issue: the dynamics of groups of people not seeing or saying things. A lot of this book is about choosing not to know things about other lives.

And then the pitch rises and something bad happens - and Darnielle is away into the history of a certain character, taking the story into a wholly new direction, employing the same rapport, the same easy style and leveraging the trust built up with the reader to tell a rather different tale, that itself loops back and becomes relevant.

It's a book where you feel that little details count, although there is never a complete picture in which you can see how they fit. A story where the present feels very indebted to the past - whether the unknown past of the Native people who gave their names to places like Tama and Sioux City and Iowa itself, or the more recent past of which Emily wonders '...what shed'd already missed, what had gone missing from Iowa before she ever got there'.

If you ever listened to those Lake Wobegon monologues in A Prairie Home Companion and thought, 'Surely there must be something darker there?' then here it is, a breathing out, almost, of the Gothic. It is in many ways a perplexing book, a tricksy book and I see that many reviewers on Amazon and Goodreads have confessed to not understanding it. I don't think I really understand it, either, but I do get it - if that makes sense. It's one of those rare books where 'understanding' is beside the point, you simply need to experience it.

Deeply weird but also deeply satisfying.

15 December 2018

Review - La Belle Sauvage by Philip Pullman

La Belle Sauvage (The Book of Dust, 1)

La Belle Sauvage (The Book of Dust, 1)Philip Pullman

David Fickling Books/ Penguin, 19 October 2017

HB, audiobook, 546pp

This is the second in my occasional series "books I bought but hadn't read yet". As with the last, the reason is the sheer mass of "now" books coming along.

For La Belle Sauvage, I did something I'm increasingly turning to - bought it again as an audiobook and listened in the car on the way to and from the station. I'm not commuting every day right now, so that means I took several weeks to hear it all - then got frustrated and devoured the final 150 pages in an evening.

The narration of this by Michael Sheen is perfect: resonant, clear, authoritative, almost as if one could hear the author writing the book aloud. Beyond that, of course, the story itself shines. As with His Dark Materials, the character of Lyra's world (for want of a better name) is felt, rather than told, from the start: that slightly sulphurous, peppery feel of a dangerous, subtly different universe. All the detail - the superficially old-fashioned Oxford, the familiar-but-different vocabulary, the terror of the Consistorial Court of Discipline, the horrific sneaks of the League of St Alexander, the vile obscenity of Bonneville - only fills in that picture and confirms it.

And so we're away, into a perfectly realised world, a perfectly realised Oxford, in the midst of, basically, a spy story. Malcolm, our hero, is a softly spoken, intelligent, resourceful boy upon whom impossible burdens will be thrust but who never thinks to refuse them. Only at one stage towards the end do we catch him thinking, I'm not old enough for this, but even then he remains brave, remains loyal. Yet Malcolm isn't a cardboard hero, he develops through this story, observes, learns, deduces, arguing things out with his daemon. His changing relationship with Alice, the strange, sulky kitchen girl from the Trout - the inn his parents keep - is a joy to behold. (And there are depths to Alice). Neither really understands or trusts the other at the start, I think, yet they find themselves having to depend on each other all the same, negotiating the relationship even amidst heartstopping dangers.

The two kids are very much at the centre of this story. There are others we see a bit of - especially Dr Hannah Relf, but also Lord Asrael, the nuns at Godstow Priory (reimagined here standing still, across the river from the Morese-less Trout Inn) - and of course Mrs Coulter Herself - but these are very much supporting parts, however important those adults may be. (They may feature in further books of this trilogy, who knows?)

Pullman does an excellent job of keeping up suspense and creating a real sense of things going on, despite our knowing, in a sense, how it will turn out - that baby Lyra will survive, that she will inherit an alethiometer, and what she will achieve in His Dark Materials. There are clearly many conflicting parties here, with the nightmarish, theocratic regime operating through numerous, often conflicting, arms and the forces of good, if I can call them that, lacking understanding of what's going on. (I say "if I can call them that" because Pullman is under no illusions that Oakley Street - his undercover resistance - will use ends to justify means when it suits them).

It's an excellent, very readable, very listenable story. My own children are grown up now but I'd happily have read this to them as a bedtime story - as I did the earlier trilogy - from say age 10 or 11 on: yes there's some swearing in here, some troubling themes but nothing one shouldn't be ready to explain (and a great deal that one ought to want to explain - Pullman's illustration of creeping Fascism in everyday life is chilling).

As the first trilogy referenced Paradise Lost, so I understand this one does The Faerie Queene. Big confession time: I haven't read that - so I can't say how relevant it is, although I can see, in the final third of the book, a rather more fantastical atmosphere than earlier, one that dallies with river gods, Fae enchanted realms. One might contrast this with the very down to earth, workmanlike tone of the early chapters - whether Pullman's writing about spyycraft or woodwork, he values competence, skill and application and at first this seems a far remove from negotiating one's way down the Thames amidst the awoken spirits of Albion. But Malcolm shows as much determination and wisdom at the latter as the former - you'll cheer him on as he manages one deadly situation after another, always gracious, modest and kind. So there isn't as much contradiction here as you might thing. take things as you find them, Pullman seems to be saying. Understand the rules. Learn how to get where you want. Do your best and never give up. Always be kind, never be cruel, never be cowardly (you might recognise that last bit and it isn't directly stated here - but is very much in tune with Pullman's themes, I think).

To sum up - I'm SO glad I finally turned to this book and now I'm just desperate for the next as, 15 years ago (15!) I waited for The Amber Spyglass.

12 December 2018

Blogtour review - Attend by West Camel

Attend

AttendWest Camel

Orenda Books, 13 December 2018

PB, e 287pp

Today I'm joining the blogtour for West Camel's debut novel Attend, publishing tomorrow. I'm grateful to Orenda Books and to Anne for inviting me to take part in this tour and for letting me have an advance e-copy for review.

I have a habit, when I review books, of approaching them in terms of how they measure up to their genre. Perhaps this is lazy, but I find it can be a way into a discussion of a book (and of course the review doesn't stop there, I generally have much more to say!)

In Attend, though, West Camel is having none of this.

The book focusses on characters, and an area, with some criminal aspects, and indeed includes crimes. But it's not a crime novel.

At the centre of the book is an unfolding romantic relationship, unlikely and immediately at risk. But it's not romance.

There is a tang of the supernatural, but the book doesn't frame that as a major source of danger or examine how the protagonists overcome it. The book isn't really fantasy or horror.

And while one character's story takes us on a journey through the 20th century (including evocative scenes set in the London Blitz) it's not historical.

Nor is it some kind of mash-up, as is currently fashionable.

|

| West Camel |

So - we have a life opening up, a life being rebuilt and a long, long life with flashbacks to episodes in Deborah's history, Camel hopping years or decades so we often hear present day Deborah refer back to events that are only described later.

This isn't the story of Deborah's life, fascinating though that might be (she starts life being brought up in a charity hospital, then is sent to an orphanage, lives as a single woman first working in factory than in business on her own behalf, survives the Blitz... always an outsider, increasingly overlooked, ignored, Deborah is a bewitching character evoking sympathy, admiration and, often surprise).

These three lives intersect, cross and double back like stitches in a piece of work in a narrative that often makes use of the symbolism of needles.

As an addict, Anne has a great deal of experience of needles - they almost cost her her relationship with her daughter Julie and her grandson. Deborah is a seamstress and has a different use for needles. Hidden away in her strange two room house on the creek, she works and works at a "winding-sheet" (I knew what a winding-sheet was so this gave me a bit of a tingle, but in case you don't I won't say) and on copying and unpicking the strange "motif" she found as a girl on a piece of stitching given her by a mysterious, dying woman. Anne has struggled to control her life, to escape from her abusive ex-husband, Mel and to rebuild some relationship with her mother and daughter. Sam is experiencing life, with great gusto, but even for him there is a darkness, a thing in his past. He doesn't feel guilty about, of course not, but which sticks with him

We see needles in other places too - such as the spire of a church, or on sale in the sewing shop. As well as causing harm, they can be used to mend, to put things right. Deborah makes Anne a beautiful dress which helps her take her place in the family. But not everything can be mended. I mentioned crime above, and at the centre of this book is a dangerous, swirling tide of male aggression and territoriality. When it all gets out of control it's left to Anne, Deborah and Sam to try and mend things.

This is a gorgeous book, full of secrets, full of unexpected glimpses of the world - light reflecting off the towers of Canary Wharf, an upstairs room glowing blue-white in the moonlight, a house where nobody expects it, the physicality of sailing in a small boat on the Thames. At the centre is a mystery which is never completely resolved - indeed I'm not we can be certain if it was there at all, which is part of the book's allure - but which drives everything. I loved the matter of fact use that Camel makes of this mystery, this possible supernatural element - it's at once throughly grounded and unremarkable and also wonderfully strange, the strangeness slipping into the misty, tide-driven marginality of Camel's Thames estuary.

I'm in danger of gushing.

I just loved this book, I wanted it never to end, I still want to know what happens next - and what happened before - and what happened in the gaps between the parts of Deborah's story we're shown. Camel's writing is immediate, compelling and vivid, creating almost a sense of the Gothic in a modern London suburb (which is perhaps as close as I'll get to answering that "genre" question").

Strongly recommended.

Buy the book!

You can buy Attend from your local independent bookshop (including via Hive Books) or from Waterstones or from Amazon.

10 December 2018

Review - The Janus Run by Douglas Skelton

|

| Cover by Andrew Forteath |

Douglas Skelton

Contraband, 20 September 2018

PB, e 297pp

I'm grateful to Saraband for a copy of The Janus Run to review.

In The Janus Run, Skelton delivers a relentless, intense thriller, full of twists, revelations and violent revenge.

Coleman Lang is living the dream. He's a successful New York advertising executive with a swanky apartment and a wonderful girlfriend (Gina). It's been ten years since he left the shadowy Janus organisation. He's put that past behind him, his divorce from Sophia is now through and all is rosy.

Then Lang falls through a trapdoor back into a world of blood, mistrust and terror.

Lang wakes up with Gina beside him in bed.

But she's dead.

And though he knows he's innocent... the signs all point to him having killed her.

Pretty soon Lang is being hunted across New York by the NYDP, Federal marshals, the Mob, the sinister Mr Jinks - and Gina's father. To survive, he'll have to remake himself into the man who worked for Janus - whatever the cost.

This is an immersive and fast paced adventure. Despite the modern setting, something about it reminded me of The Thirty Nine Steps. Like Buchan's hero Hannay, Lang has a past as a man of action, and like Hannay, he must clear his name in circumstances that are, to begin with, completely murky. And, again like Hannay, he's supported - or hindered - by an ill suited partner he's nevertheless forced to cooperate with. For me that relationship, founded on a total lack of trust between two men from different worlds who are nevertheless forced to accept they have a great deal in common, was the strongest part of the story, at times even slightly amusing.

I'm a bit wary in general of stories which use the death of a woman to motivate a male character, and it would be good to have seen a living Gina in this book (especially given what we learn about her) but I feel that in The Janus Run Skelton has provided a great deal more to drive events than that: Lang's Janus experience, and the underworld links that complicate things, would have snarled him sooner or later in any case.

The plot doesn't just follow Lang and his associates but also spends a fair bit of time on his NYPD opponent, Rosie Santoro, and her frustrations with the job as well as her bonding with US Marshall TP McDonough (who has her own cross to bear in the form of obnoxious colleague, Burke). Santoro has a lot to do here as the body count grows and comes across as cool and capable. Santoro is a complex character who I sense we'll see more of if Skelton follows up this story.

Given I'd previously only encountered Skelton's writing set in Scotland, I did wonder to start with whether his New York would convince but it rang very true to me (disclaimer: it's not a place I know myself, so I may be wholly off the point here but it fits my idea of New York.

The book packs a great deal in given it is fairly short, so it's pretty much nonstop action (I lost track of exactly how many deaths take place) and really deserves to be read in a single sitting: watch out if you've got any urgent appointments, you may end up missing them! There is though much more to it that an extended chase/ shootout. The Janus Run has a delicate and ravelled plot, with - as Lang realises towards the end - many wheels turning within other wheels. And some of which continue to spin when we reach the end, holding out the promise of a sequel which I for one would be very keen to read.

You can buy The Janus Run from your local independent bookshop via Hive Books, from Waterstones, or from Amazon.

For more on the book see the publisher's website here.

7 December 2018

Review - Lies Sleeping by Ben Aaronovitch

|

| Cover design by patricknowlesdesign.com |

Ben Aaronovitch

Gollancz, 15 November 2018

HB, 404pp

I've made a little space now to read "bought" books - and hopefully will do more over Christmas, reducing the H&S risk from that TBR potentially falling.

The first of these is quite recent - the latest in Ben Aaronovitch's Peter Grant series. I have no illusions about ever being high enough in the blogging food chain to request a copy of a book such as this, but I'm still smug, because I do have a signed first edition of the original Rivers of London, so there.

Warning for mild spoilers for the previous books - and also that this review will make little sense if you haven't read them yet (but if you haven't, you really shouldn't be starting here, should you?)

Like the previous books, it's eminently readable: if you start this you'd better have blocked out your day because you'll get nothing else done till it's finished. Indeed I think the adventure may actually flow a bit more smoothly than it has in the past, with Peter and the team on top form and a defined, targeted operation against the Faceless Man in train rather than the normal series of seemingly unconnected crimes that eventually join up. It's "intelligence led" policing (cue some subtle Met humour as you can imagine...) designed to draw out the target, not wait for them to act.

Other things are also a bit different. While The Folly has always been part of the Met, it tended to be pretty empty, more of a bolt-hole for Peter, Molly, Nightingale and Toby than a functioning police station. Now that's changed - they even have whiteboards! (The plumbing is as dodgy as ever, though). And it's not just Muggle cops either - in various different ways, a number of Peter's colleagues now have, or are developing, magical abilities (apart from Lesley May, who went over to the Dark Side several books ago). So while we gain something in teamwork and efficiency, there's a but less, perhaps, atmosphere Folly-wise. That's more than made up for by the extraordinary focus of this book - like its predecessors - on London and London history, in particular the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and the Roman origins of the City.

More importantly, perhaps, I think this book has a darker atmosphere than the earlier ones. We are closer to seeing exactly what the Faceless Man is up to, of course, but there are other strands too. Lies Sleeping presents Western magic (perfected by Isaac newton) in a somewhat critical light. There is a story from the Old West of Newtonian magic being used to bring down a Native practitioner, and Peter muses on what his predecessors at the Folly may have dome themselves in the service of the Empire (I will remind you here that Peter is Black - I really enjoy him introducing characters he meets as white, where appropriate). This is underscored by allusions to Tolkien, of all writers. There is a running joke equating the Folly to Mordor. Of course one does not simply walk into the Folly... but also when a base of rival (cast out?) magicians is discovered, a chapter title - "The Flattery of a Slave" - refers directly to the description of Isengard in Lord of the Rings (implicitly making the Folly the Dark Tower). And more prosaically, in another strand, we see some of Peter's colleagues affected by stress, with a concern over his own wellbeing. And there's even a menacing prophecy (in Latin, natch...) suggesting no good may come to him.

If that makes it all sound introspective and doomy, it's really not, though the story is perhaps slightly more edgy. Aaronovitch shows here - as he has before - a rare ability to portray the mundane and real (all that police procedure, which reads as very accurate, though what do I know?) alongside and sometimes entwined with, the metaphysical (the magic, the London history all those hints of darkness, the mystery that's Nightingale, and much more). It's a mixture that makes for an entertaining story, but also has a sense of depth, of seriousness, of there being a point. And that's only enhanced by the normal shenanigans with the River gods and other strange denizens of London.

Basically, this is Aaronovitch in stonking good form. The book is a delight to read and it's great that, so far in, the series shows no sign at all of flagging.

3 December 2018

Review - Supercute Futures by Martin Millar

Supercute Futures

Supercute FuturesMartin Millar

Piatkus, 30 August 2018

PB, 228pp

I'm grateful to the publisher for a review copy of this book.

In a near future where the earth has been blighted by a series of disasters - human caused and natural - corporate culture dominates, with the top 19 conglomerates - the "C19" - at the top of the pile. Among these is Supercute, the empire founded by teenagers Mox and Mitsu in their bedroom, using an iPhone to create their own show which would feature not only fashion and music but maths, science and philosophy.

But that was decades ago. While Mox and Mitsu still present their show they're now at the head of an enterprise that not only provides clean water to near starving population, but makes arms. That doesn't just project an image of CGI "cuteness" but builds over nature reserves. That has virtually dropped its educational mission, and even has reserves of troops.

And the Supercute girls are barely human, having received augmentation after augmentation.

This was a grim view of the future indeed, and yet - in the obsession with marketing, glamour and image - rather plausible. In particular I found it didn't take a lot of imagination to accept the enfeebled governments, impoverished public realm and corporate chicanery. The latter is a key ingredient of the book, as a rival corporation, led by the ridiculous Moe Bennie, essentially hacks into Supercute to stage a hostile takeover. "Hostile", in the work, meaning something ultimately enforced by private armies, drones and missiles. Mox and Mitsu are challenged as never before by this, thrown onto the ropes and having to fight back for everything they've built.

That makes for a story which is essentially one drawn out chase and revenge sequence, mainly taking part in the abandoned, radioactive tunnels of the London Underground and in the various virtual "spaces" where Supercute and the other corporations hang out. The girls have to recruit some VERY disgruntled ex employees to help them, as well as some of the legion of Supercute Superfans around the world.

This was where the story got a bit squirmy for me, as I didn't really get the motivation of the ex-employees - Mox and Mitsu aren't, and don't really try to be, very persuasive to those who already have reason to distrust them - and the idea of billionaires recruiting help from the impoverished teenage girls living in refugee camps who seem to be Supercute's key demographic isn't really a very nice one. But I think that's possibly the point. When I first started reading the book I felt that M&M (sorry, I can't help that) were a bland and characterless pair, but I think what the book reveals is that's just a (cute) front. Underneath - and once out of the studio - they have bags of character, it's just they're not very nice at all.

Indeed, if you knew at the start what you learn by the end, you probably wouldn't care at all what became of them. The Supercute empire, which started with a commitment to real good - relief of suffering, empowerment, an educational purpose - has become nothing more than part of the corporatist apparat keeping the struggling masses down. Despite the intermittent attempt of the girls or of others to excuse themselves, it's clear there's been no real attempt to stand against this and I fairly quickly began to ask why should I care about them at all. But by then a VERY hectic chase was under way with it's own momentum.

The other difficulty I had with the story was the unlikely sequence of disasters which seemed to have befallen Earth to make everyone so miserable. Apart from understable things like global warming, and wars, we hear of a dramatic collapse in the ozone layer, numerous volcanic eruptions and tsunamis, accidents involving nuclear waste which have left much of the Thames Estuary irradiated and even a supernova. There is also talk of several "impacts" which I took to be meteorites or the like. I was waiting for some kind of rationalisation of this - have Supercute and the other corporations taken advantage of all these calamities, or did they somehow cause them? It seems too much, and too varied, for coincidence, and actually I think the global prognosis from what we already know is grim enough to motivate this future without the need for extra disasters.

So I do have some reservations. (I was also rather gobsmacked by the ending - Millar delivers a truly "WTF happened there?" moment which will I think annoy those who think they're going to get a neat, clear conclusion. But I don't mind that, though I am still puzzled. I won't spoiler by saying what I think the ending meant, but if anyone out there has any ideas, I'd be happy to discuss).

That said, though, it's not a bad read, it has terrific pace, it is short (I can imagine some authors making this two or three times as long, which wouldn't work at all) and, in its own terms, plausible.

1 December 2018

Review - Beyond the Bay by Rebecca Burns

Beyond the Bay

Beyond the BayRebecca Burns

Odyssey Books, 19 September 2018

HB, e 244pp

I'm grateful to the author for an e-copy of Beyond the Bay for review.

My review

Set in late 19th century New Zealand, this is a story of two sisters, Isobel and Esther. Isobel emigrated from England ten years earlier - now Esther is coming to join her in the well-appointed townhouse she's been told about in Isobel's letters.

Reality is rather different.

Isobel, or Bella as she's now called, doesn't live in a fine house but in a one-room cottage set between an abattoir and a carpenter's workshop. The walls are papered by old newspapers gummed down with flour and water, and Esther will be sleeping in a bed made from packing crates. Worse, Isobel's husband Brendan - who seemed so dashing and enchanting back at home - has become (or always was...) abusive drunk. For many, life is hard in New Zealand, and it's difficult to find contentment when everything is being judged against a rose-tinted memory of "home". The place seems to work on the character, exposing underlying meanness in some and generosity, empathy and warmth in others. Ten years in New Zealand have "formed" Bella from Isobel - there are many references here to the making of new women, as with Isobel when subject to "The rattle and surge of carriages and Cobbs".

Esther brings her own problems with her, though, and if she thought that Isobel would have the money or the time to help sort them out - well, she was wrong.

I loved the way that Burns sets up the situation of the two sisters, both looking back to their lives as girls and telling the story now from both their perspectives, sometimes carrying on the same incident or event from one to the other so that we get a compound view. This also gives plenty of scope to explore what went wrong and to explain why the two are somewhat prickly with one another. There are lots of agendas and secrets here, but they're set against the crushing demands of living in a hard world - the colony isn't a forgiving place, even if it has a fancy new Opera House and a lively politics. (The background to the story is the struggle for womens' suffrage, Isobel having joined the campaign much to Esther's amazement).

The story is set in the same "world" as Burns' earlier collection of interlinked long-short stories, The Settling Earth, (my review here) with one or two of the characters from there mentioned and a particular incident forming a counterpoint to some of the themes here. Burns also makes an allusion to the role of her women ("They've worked with men in settling the earth"). That means the reader, if they know the earlier stories, can't help but feel a certain depth, a richness, to the world described here (though you don't need to have read them to follow Beyond the Bay).

Without being preachy, this book starkly illustrates the dilemma of so many of the women portrayed, whether they are penniless settlers, have inherited or been gifted a bit of money, or have an apparent degree of privilege with wealthy parents. Despite being on the cusp of winning the vote, they are controlled, manipulated or outright bullied by men of all types, denied choice and agency and - as illustrated here in a heartbreaking scene - literally unable to say "no". The book also explores the solidarity and support that's on offer from other women, but makes clear there are those who would deny it, especially when personal motives and desires complicate things.

If the first half of the book is dominated by the claustrophobia of that cottage, the second part opens things up more with a dangerous journey to a remote farmstead and a bit of a theme of people (women especially) being able to enjoy a degree of freedom and opportunity ("...in New Zealand women built homes with their bare hands and, in the back country, ran farms and homestead...") I won't say too much about this part because it would be slightly spoilery to give away the reasons for this, but the journey does give that part slightly more structure and shape and there's quite a bit of action. The ending felt to me as though Burns was leaving things open for a sequel, which I'd certainly read - these are characters who grow on you and who you want to spend time with.

Overall this is an absorbing read, wise and human where it exposes the truth of womens' lives and also providing a warts-and-all account of the early years of settlement in New Zealand. I'd strongly recommend it.

About the Author

Rebecca Burns is an award-winning writer of short stories, over thirty of which have been published online or in print. Her short story collections - Catching the Barramundi and The Settling Earth - were both longlisted for the prestigious Edge Hill Short Story Award, the UK's only prize for short story collections. The Bishop's Girl, her first novel, was published in September 2016. Artefacts and Other Stories, her third collection of short stories, was published in September 2017. Beyond the Bay is her fifth published work. She was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2011, winner of the Fowey Festival of Words and Music Short Story Competition in 2013 (and runner-up in 2014), won the Black Pear Press short story competition in 2014, was shortlisted for the Green Lady Press Short Story Competition in 2015, and was either short or longlisted for the Evesham Festival Short Story Competition, Chipping Norton Competition and the Sunderland Short Story Award in 2016. She has been profiled as part of the University of Leicester's 'Grassroutes Project'-a project that showcases the 50 best transcultural writers in the county.

Buy the Book!

You can buy Beyond the Bay from Hive Books, Waterstones, Amazon or from the publisher.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)