Beyond the Veil: New Horror Short Stories

Edited by Mark Morris

Flame Tree Press, 26 October 2021

Available as: HB, PB, 320pp, d

Source: Advance review copy

ISBN(HB): 9781787584631

I'm grateful to the publisher for an advance copy of Beyond the Veil to consider for review and to Anne Cater for inviting me to join the blogtour.

Following on from last year's anthology After Sundown, editor Mark Morris's new collection of stories Beyond the Veil is an eclectic sampling of modern horror, touching upon so many varieties of the genre beyond the spooky house or violent slasher.

In some of the most shocking stories, the darkness comes from bleak relationships or social isolation rather than the overt supernatural. Consider Soapstone, for example, in which Aliya Whiteley looks at the aftermath of a funeral. Jen has chickened out from attending her friend Sam's send-off. In a sensitive and poignant (and sympathetic) examination of death we see something of what he meant to her, but her reaction seems extreme even before taking a turn for the weird and the horrific. This does though seem to exemplify something about modern society and its capacity for distraction. One of my favourites in this volume.

Or Away Day by Lisa Tuttle, which updates an old folk motif - I won't say which for fear of spoilers. I will just say that the horror in Kirsty's team-bonding weekend seems to lie in her dreadful colleagues and frosty husband - but maybe there's worse in the woods?

Or look at A Mystery For Julie Chu, in which Stephen Gallagher gives us what could almost be a pilot for an urban fantasy series. Julie makes a bit of money on the side by spotting useful stuff in car boot sales and selling it on to auction houses. She seems to have a knack for spotting things that will command a good price for, well, esoteric reasons. Things that aren't auctioned publicly but which will find just the right client. But that can lead to some dark places and reveal some dark secrets. Does the horror come from what's revealed here, or simply from the way it happens? Either way, an enjoyable, twisty and well realised tale.

Clockwork by Dan Coxon is also an eerie little tale, a story of abuse, revenge and obsession in a potentially slightly steampunky alternative present. I loved what it doesn't tell us - why, after a pitiful funeral, a young woman is so eager to dig up her father's rhododendrons. She finds something down there, but was she looking for it? Is what happens after intentional? That mystery adds to the claustrophobic texture of a story set largely in one down-at-heel home. I should say, to the multiple mysteries: we don't get all the answers.

There are also more traditional stories. For All the Dead by Angeline B. Adams and Remco van Straten takes place in the Saltcamp, a small fishing village on, I think, the Dutch coast. It's an atmospheric, sea-drenched story focussing on young Hanne whose father was lost, with many other men of the place, in a catastrophe at sea. The story is steeped in the superstition of those whose lives depend on the unpredictable sea. It's a place and time where customs are fiercely protected and change is distrusted. A real classic ghost story, to read on a dark night when the wind is growing. And years ago (before I was blogging) I loved Jeremy Dyson's collection The Cranes that Build the Cranes - it's great to see a new short story form him. In Nurse Varden, Brosnan needs an operation on his knee, but a pathological fear of being unconscious holds him back. Seeking therapy to overcome his problem, he tries to recall his earliest memory... from what seems liken a simply phobia, Dyson creates a really creepy story of compulsion, bristling with suppression and darkness. A real chiller.

Those are only some of my favourites. Mark Morris has assembled stories from more than twenty writers, some I'd encountered before but most of whom were new to me. It's one of the joys of a collection like this that one will encounter new writers and new writing and, prompted, look out for their future appearances. I think there will be something here for everyone.

In The God Bag by Christopher Golden, an elderly woman, suffering from dementia and other illnesses, draws comfort from what she refers to as her "God Bag" - which contains scraps of paper on which she's written heartfelt prayers, both weighty and trivial.

Caker's Man by Matthew Holness is a really dark story in which so much might be taken more than one way. An innocent gift of cake? A lonely neighbour who simply want to be friends with a young family? Where is the line crossed, and how exactly? Holness's story expertly keeps one doubting, from that first line - 'They keep asking me...' Who are asking, and why, and why don't Toby's answers satisfy?

Priya Sharma's The Beechfield Miracles is set in a new future, decaying UK ('Brexit Britain. Blackout Britain. Britain on the brink.') in which Rob Miller, a notorious journalist, sets out to investigate one of the vestigial reasons for hope - a (perhaps) miracle worker who's giving the poor new hope, rescuing the vulnerable and, we learn, punishing the wicked. What's her secret? We're left wondering if the horror is what surrounds,. or what may come.

The Dark Bit by Toby Litt features a comfortably-off urban couple, Pyotr and Anaïs, who Pyotr admits won't garner sympathy (mid-thirties, corporate... South London') whose lives are about to be seriously derailed (or have been - for reasons the story makes clear, Pyotr is recalling what happened). It's an intensely creepy story of something going gradually wrong. Whether in reality, or in a kind of collective delusion, is never clear but, oh, it's scarily plausible and made me want to switch all the lights on and sweep out all the dark bits ion my own home.

In Josh Malerman's Provenance Pond, Rose plays by a pond at the end of her garden. She meets imaginary friends there. All seems harmless enough, but her parents, and particularly her father, object, telling her she should be growing up. Yes, Rose's friend, especially Theo, seem a bit weird but can this justify what her father does? But then Malerman pulls away the rug, twisting things round so that the whole story appears in a new light, commenting on the relationship between childhood and adulthood and the peculiar dynamics of families. A moment of enlightenment but still a very scary one!

The Girl in the Pool by Bracken MacLeod is a third story exploring the fear and peril to be found in water - but we move from the dark and cold and wind of the Old World to the heat and dappled light of the new, and from seasalt to the chlorine of a swimming pool, as Rory sets out to burgle a wealthy mansion. He's done his homework and nobody should be at home, but makes a nasty discovery. A bitter little example of that theme of classic horror, the trespasser who gets more then they expected, I found this one enjoyable on every level.

If, Then by Lisa L. Hannett is a clever take on a fairytale theme - the briar-encrusted castle, the sleeping princess, the faithful gardener are all there... as are the nobles clearing the thorny growth from the enchanted building. But nothing is quite what it seems here. Hannett pivots her story from charming and romantic to horrific and... other things I won't mention for fear of spoilers... in the blink of an eye. The sounds of the exes from outside may build tension, but it's what's going on inside that brings the real dread.

Aquarium Ward by Karter Mycroft evokes some of the feelings of the current pandemic - the new condition springing from nowhere, overwhelmed medical staff and and an atmosphere of frenzy and even suspicion. But with the presence of mysterious law enforcement operatives hauling away victims, a fatal condition and a miraculous cure, one overworked doctor begins to think they see a pattern in events... grim, heart-thumping horror in this one.

In Polaroid And Seaweed by Peter Harness, my heart really went out to sad little Danile, a boy who never seems to get a break in life. The horror, again, seems to come from humdrum things: a difficult home situation, horrible kids at school who scent blood and go after him like a pack. But, again, there may be worse things at sea? This one definitely left me wondering, and thinking.

Are you intrigued by abandoned urban sites - lost metro stations, for example? If so, Der Geisterbahnhof by Lynda E. Rucker is for you. Set in Berlin, this sees Abby's past reach out to her - in a city that has so much past. Rucker seems to be able to evoke all those layers, all that horror, as Abby navigates her way around the city, eventually receiving an invitation that she she can't quite see her way to refusing. Chilling and unusual.

Arnie's Ashes by John Everson evokes the sticky, seedy horror of the sprawling modern city - the things that may breed in darkness in the corners of the "adult" club, its impact on those living precarious lives in cheap lodgings, and the means that may need to take top defend themselves. Grimly funny, this is monster horror a million miles from the gothic castle or whispering wood.

In A Brief Tour Of The Night by Nathan Ballingrud, we see something of the same world as in Arnie's Ashes - desperate men and women living on the edge, always one payday away from ruin, but the story reminds us that there are others caught up in that world too. Allen, a figure hated and derided in his community is able to see ghosts. But what does he seem to welcome that? Who does he want to come to him on his nocturnal walks?

In their very different ways, though, the two stories that close the book encapsulate for me the essence of horror. The Care And Feeding Of Household Gods by Frank J. Oreto was I think the most horrific story in this book. It's hard to say anything about it without giving too much away - as the title hints, it features a particularly ancient superstition which ought to hold no traction in the modern day but which surprisingly does. Then Oreto takes that idea and lets it run. Where might we end up...?

Finally, Yellowback by Gemma Files is one of several stories here with a pandemic influence. Women are being struck down by a strange skin condition which results in their faces scabbing over, ending up producing a yellow-brown, chitin-like mask whose detaching marks the end of a painful and unpleasant illness, almost invariably resulting in death. The rapid speed of this affliction has produced all sorts of ructions in society, including firing misogyny, but as Files hints there's something else at work besides a new pathogen. The attentive reader may notice implicit references here to something older, deeper and distinctly creepy.

So - overall, this is a very strong collection indeed, one I'd unreservedly recommend.

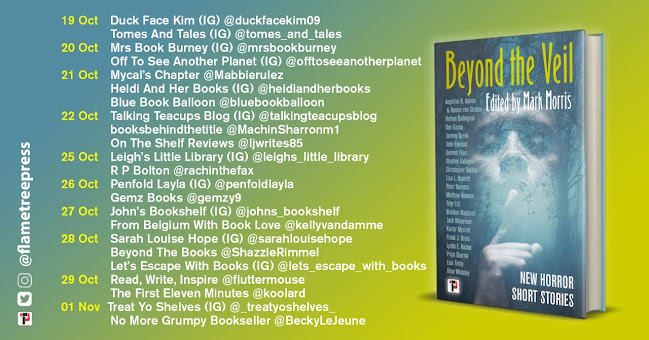

For more information about Beyond the Veil, see the publisher's website here. As well as visiting the other stops on the blogtour, which are set out on the poster below.

You can buy Beyond the Veil from your local bookshop, online from Bookshop dot org UK, from Hive Books, Blackwell's, Foyle's, WH Smith, Waterstones or Amazon.